Free Naloxone Kits Dispensed in Emergency Department – No Questions Asked

The emergency departments of Elizabethtown Community Hospital and its Ticonderoga campus recently began providing free naloxone kits, with the drug used to reverse the effects of an opioid overdose, to anyone who wants them – no questions asked.

David Clauss, MD, medical director of both emergency departments, appreciates more than the kits’ potential to save lives, whether they’re given to individuals with opioid use disorder or to family members or friends. An equally important benefit, he says, is the opportunity for hospital staff to connect with patients with opioid use disorder when they come into the emergency department, establish trust and ideally encourage them into treatment.

“Providing the naloxone kit is a very clear way to say that we’re concerned about this, that we want to help you,” Dr. Clauss says.

Naloxone, often sold under the brand name Narcan, can prevent overdose from opioids such as heroin and fentanyl by blocking opioid receptor sites in the brain. It would be used when a person is showing signs of overdose.

The kits come courtesy of a grant from the Alliance for Positive Health, an organization based in Albany, N.Y., that focuses on improving the lives of people with HIV/AIDS and other chronic diseases. The free offering of naloxone to opioid users and those close to them are among many initiatives that Elizabethtown Community Hospital (ECH) is embracing to fight the opioid epidemic, Dr. Clauss says. Both ECH and its Ticonderoga satellite hospital are part of The University of Vermont Health Network.

Dr. Clauss’s primary goal when caring for patients with opioid use disorder is to erase judgment and stigma, he says. Those attitudes “are alive and well, and they are barriers to care,” he says.

The Naloxone kits are one way to address that, he says. “We want to create an environment where people know that individuals affected by opioid addiction are welcome, that we want to help them, that we are open to helping them and that we are not going to be judgmental in doing so.”

By using that approach and influencing other emergency department staff to adhere to it, Dr. Clauss continues, “my hope is that it’s going to make individuals more willing to actually seek help.”

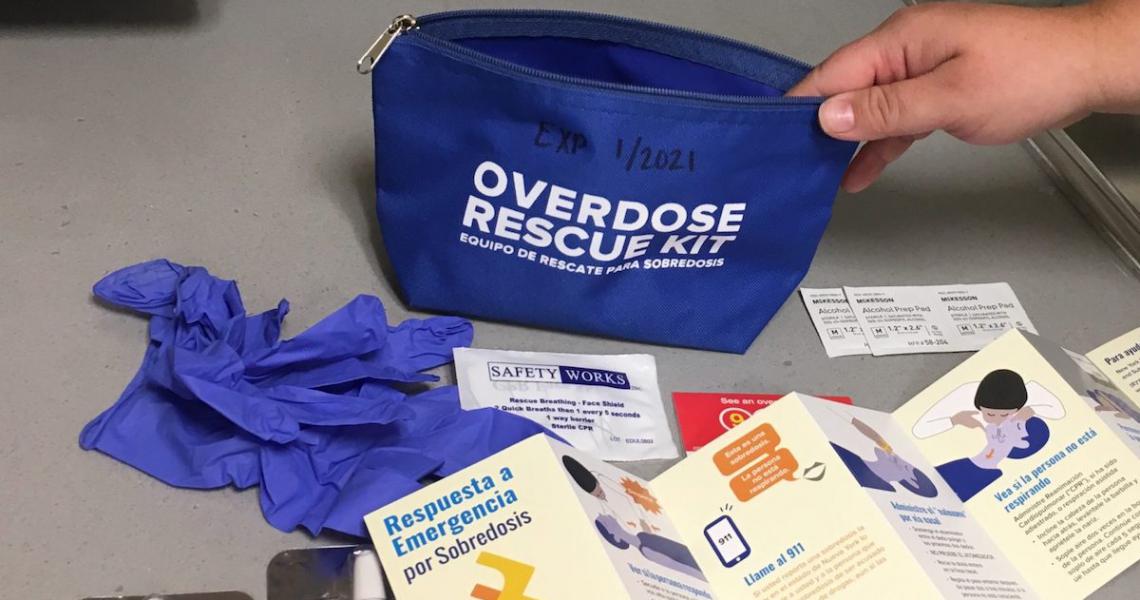

The kits offered in Elizabethtown and Ticonderoga include a nasal spray of naloxone, breathing masks and an educational brochure. Emergency department staff will give those who request kits a brief training to help them recognize signs of overdose and administer the naloxone.

They can return used naloxone kits to the emergency departments or to an Alliance for Positive Health office, including one in Plattsburgh. Elizabethtown Community Hospital also provides safe disposal bins for opioids and other prescription medications at both campuses.

People struggling with substance use disorder often make first contact with a medical professional when they come to the emergency department with a specific problem – an overdose, an infection from their drug use or a violent incident related to their addiction, Clauss says. He and his emergency staff reach beyond that and encourage patients to recognize their larger issues and take steps toward recovery. A nonjudgmental attitude can make all the difference, he says.

“In emergency medicine we see people at their worst moments, and in those moments we have a choice to make: Do we shame this person while we’re providing care, or do we make this as welcoming an environment as possible and try to really optimize the level of care that we can provide?”

In a rural area like Elizabethtown, the emergency department sees relatively low numbers of patients with opioid use disorder and has relatively fewer providers to treat them. Nonetheless, Dr. Clauss says, the hospital is committed to implementing practices that are proven to help people struggling with addiction.

Among those efforts, the hospital is building bridges in the community with other organizations and other medical providers. Dr. Clauss said he’d like to establish a more robust system of physicians waivered to offer buprenorphine, one of the medications that blocks the symptoms of withdrawal from opioids, so patients can receive treatment closer to home.

The region’s medical community, particularly those in emergency medicine, can and should lead the way in offering open, unbiased care and connection for those struggling with the disease of addiction, Dr. Clauss says.

“It’s our job to figure out how to address their issue most constructively with respect and with compassion.”

This story was reported by Carolyn Shapiro, with the UVM Health Network.